The following is

translated from the brochure of a cultural and art exhibition “Stolzenau im

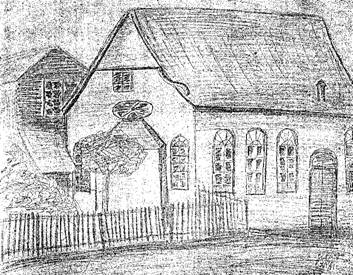

Zentrum” (Stolzenau in the Center) that was held in November 2000. Except for an old drawing of the Stolzenau

synagogue, there are no pictures of the former Jewish community. Therefore, the following essay was presented

in the exhibition as a testament to “a time that must never be forgotten”.

The name Michael Künne

is included in the introduction, but it is unclear whether he is the author of

the essay.

The endnotes are

comments inserted by the translator.

The Jewish Community in Stolzenau

|

|

This picture of the Stolzenau synagogue was drawn in 1920 by Gertrud Witte, who was then 13 years of age.

|

In former times, in addition to the

Evangelical-Lutheran community and the Catholic St. George’s community, there

was a Jewish community, which existed up to the beginning of the Second World

War. Their history is to a large extent

unknown, and can be only incompletely portrayed. The only tangible memory that

remains is the Jewish cemetery at the town’s boundary with Schinna. This burial place existed already in the year

1771[1],

as can be seen from a survey map of the Principality of Hannover. At that time the highway passed the cemetery

on the east side. However, about 100

years later it was moved to the west side.

At this time [i.e. 1770’s] there were 4 Jewish families in

Stolzenau. This information can be found

in a document called “Versuch einer Beschreibung des Amtes Stolzenau”

(Attempt at a Description of Stolzenau) by Joachim Plate. It says, on page 202: “The resident Schutzjuden

(Protected Jews) in this hamlet, who have middle-class houses, consist of 4

families. In accordance with the rescripti

regiminus (administrative order) of 24 Nov 1755, Levi Markus’ son Marcus

Levi’s partial protection has expired following his father’s death, since the

son can step into the father place. The business dealings of the Jews are of so

little importance here, that they can hardly make a living; especially since

Christian businesspeople in these places do not have any problems.” That was about 1760[2].

In 1810 it was officially reported that out of 1069

inhabitants in the hamlet, 48 were Jews. This

increased to 79 in the year 1830 and to 96 in the year 1833, which

constituted about 6% of the population.

This increase can be understood if we look at events beyond this small

place. In modern times, which began with

the French revolution in 1789, Jews achieved civil rights on an equal footing

to the national inhabitants in many countries.

In France this occurred already in

1791, in Germany in 1808, and in Prussia by the edict of 11 Mar

1812. This was accompanied by the

requirement that they had to use permanent surnames, and to use the German

language, and Latin or German writing[3].

Thus many Jewish families stopped using confusing mosaic names and requested,

against payment of a fee, new German-language names. Thus many new names

emerged like Löwenstein, Blumenfeld and Rosenbaum.

A certain liberality and a legally authorized

right of domicile allowed the local Jewish community to increase to 103 in 1839

and to 116 in 1852, equal to 7.5% of the entire community. It is therefore

understandable that in 1829 permission for the accommodation of a Jewish

teacher was granted and a few years later, in 1835, approval was sought from

the authorities in Hannover for the construction of a new synagogue for the Jewish

community. Some of the documents are in

the State Archive in Hannover under the Register No. 80 Hannover 1, Verwaltung der Ämter, Amt Stolzenau Nr.

103—112.

Another source is the annual reports of mayor

Oldemeyer, who occasionally provided remarks in addition to purely statistical

data. Thus on 18 Nov 1836 he wrote:

“The Police Superintendent will report about

the increase in the local Jews. This

year’s count resulted in 98 souls, i.e. 1/17 the the population of

Stolzenau. They live moderately, are

industrious, entrepreneurial and careful, and thereby they acquire fortunes.

Their dealings in the surrounding villages could probably be limited to

something that is best for the farmers. Their past conditions in this State are

well-known, their future is still unknown. Hopefully the completion of

construction of their new temple and school will have a positive effect on all

here in terms of education and moral

improvement.”

This new temple stood until the year 1938 at

Talstrasse 7 opposite the Münchhausen garden. It was a staid building. In the

lower room at the right was the bare and seemingly inhospitable Jewish school.

It was attended in 1875 by 11 local children and 3 others from Leese. It

existed until approximately 1925, when it was dissolved because the number of

children became too small. The 4 pupils were transferred to the local

elementary school and the teacher Frühauf was sent to his hometown in Hessen.

We infer from the annual report of 1841 that

the Jewish community consisting of approx. 100 souls made its living from

butchering, grain, wool and trading in hides.

In the year 1843, in his report to the Royal authorities, Oldemeyer

expresses his opinion in somewhat more detail:

“Due to

the new law concerning the legal rights of the Jews, we were forced to accept

several local Schutzjuden as citizens and to give others their

independence. Since the Jewish character has remained unchanged for thousands

of years, the current improvement in their legal rights will probably not

benefit the financial circumstances of the Christian population, and the only

reward to the latter will have been to have shown a general love for humanity

…”

These remarks of Oldemeyer’s arise not from an

antisemitic attitude, but from his concern about the alienation of some

occupations, since already in 1823, in a count of businesses, it was shown that

there were 2 Christian butchers and 6 Jewish butchers[4]. In the mid 1840’s the Jews possessed 8 houses

and about 10 acres of garden-land.

While the number of the hamlet’s

Evangelical-Lutheran inhabitants declined from 1651 in 1842 to 1370 in 1858,

the number of Jewish inhabitants remained at 100 and more. At this time there were only 10 Catholic

citizens.

From an old registry of houses the former house

ownership and change of ownership are precisely evident, and it is amazing to

see how large the change is, in terms of the Jewish proportion. In the space of approximately 50 years, Jews

went from owning hardly any houses in Stolzenau, to owning 35[5]. At one time the following houses were owned

by Jews:

Lange Strasse: Nos. 2, 4, 9, 10, 17, 18, 19,

21, 24, 25, 26, 34 and 48;

Hohe Strasse: Nos. 1, 17, 33, 35 and 60;

Krumme Strasse: Nos. 4, 5 and 6;

Bahnhof Strasse Nos. 8, 13, and 15;

Schul Strasse Nos. 2, 3 and 8;

Am Markt: Nos. 1, 3 and 9;

Weser Strasse: Nos. 2, 4 and 6;

Jungfernstieg: No. 2; and

Der Allee: No. 5.

The names of the purchasers are known. For example:

1832 M. Lipmann, Lange Strasse No. 9

1852 ltzig Lipmann, Krumme Strasse No. 5

1853 Salomon Elle, Schul Strasse No. 3

1854 Levi Löwenstein, Lange Strasse No. 17 (Thams & Garfs)

1855 S. Goldschmidt, Am Markt No. 3 (Stühmeyer)

1855 Widow Hildesheimer, Am Markt 9 (Strohmeyer) (known to old Stolzenauers as

Zärchen-Sarah[6])

1856 M. Lipmann. Lange Strasse No. 18 (Destroyed by fire. Today this is a garden)

In the course of the years many Jewish families

moved away or died out. Some names

disappeared, e.g. Hammer, Levi, Markus, Wenkheim, Weinberg and others[7],

and the number of Jews decreased significantly:

1880 — 100

1890 — 90

1900 — 70

1920 — 60

1925 — 50

1933 — 25

and the number then decreases to the point of complete disappearance of the

Jewish population.

The author of “Erinnerungen eines alten

Stolzenauers” (Memories of an Old Stolzenauer) from the middle of the last

century, in his thoughtful descriptions, mentions his Jewish fellow citizens

here and there. He writes, for example: “Opposite the pharmacy, by Baker

Könemann, is the Blumenfeld house. The

two Blumenfeld brothers, Wolf and Selig, settled in this house around this

time. Both have a dignified, military

appearance. When they visit their customers, dressed in snow-white jackets with

shoulder straps, and their bright sharpening steels in a pearl-stitched band at

their sides, no-one can compete with their appearance. Except, perhaps, their sister Röschen, who is

always known as “Beautiful Röschen”. She

overshadows her brothers in terms of looks, and has earned her nickname

(Blumenfeld’s butcher shop is today the Hahlbaum shoe shop).

Or he

writes: “Beyond the Rectory at the corner of Schul Strasse, we come to a tiny

little house, and at the door from early to late, year out and year in, stands

a man with a short curved pipe between his teeth. The pipe is never extinguished. It is Benni, Benni Hildesheimer. He inhabits this little house with his

brother ‘Benni’s Michel’ and his mother ‘Benni’s Mutter’. That the family is

called Hildesheimer is known only to a few official persons. Everyone knows them only by the

aforementioned names. And who doesn’t

know Benni? He is completely

untypical. He has inherited none of the

drive and business acumen which normally distinguishes these people. It is reported that he is an important horse

connoisseur. It is also said that now

and again, he plays the role of secret broker in horse trades. But these are just assumptions.” (The “Benni

House” was later enlarged - today it is the Salon Klinke)

“At the corner of the Krumme Strasse is the

family Löwenstein, but they are always called

‘Jakobs’. It is, at this time, the largest butcher shop in the

town. Father Jakobs, a short stocky

gentleman with a ruddy complexion, dressed in a short jacket of printed cotton,

rules over his group of strapping sons and daughters in patriarchal

manner. Markus and Itzig, in particular,

have remained in my memory. Their white

jackets possibly exceeded the whiteness of those worn by the Blumenfeld

brothers”. Just like the author of the “Erinnerungen”

many old Stolzenauers who were born around the turn of the 20th

century, retain living memories of the subsequent generation of the Jewish

community. Human peculiarities and all

too-human features and weaknesses of some of the Jews of former times are

smiled at, and some small anecdotes could be written.

Naturally, there are also less pleasant

memories, and only two are mentioned here. There was the wretched “Schützenfest”

affair of 1924, when the wool merchant Gustav Lipmann assumed the role of

“king”. He spent quite a lot of money,

and experienced the embarrassing situation, when the parade of the color

bearers of an association was called, that they refused to carry the flag

behind a Jewish king. On another occasion, a new member of the MGV (a

choral association), named Hellwinkel, introduced antisemitic attitudes for the

first time in that group, and the two outstanding tenors of the MGV,

Selig Blumenfeld and Adolf Löwenstein, felt no longer welcome in the company of

their old choir brothers, and so they stayed away from the association. They

did not return, even when Hellwinkel left Stolzenau.

The fate of the Jewish community after 1933 is

described only briefly:

From a document dated 6 August 1935 by the OG

(local party leader) of the NSDAP (Nazi party) to the municipality:

- No Jew may acquire a house or land in Stolzenau.

- No craftsman, businessman or member of the Volk (German

people) who still traffics with Jews or supports their business

activities, may do any work for, or supply, the municipality. Purchasing

from Jews means betrayal of the Volk and the nation.

- Signposts are to be placed at all entrances to the town with the

following words: Jews are not wanted here.

- All members of the Volk are encouraged to read the newspaper “Der

Stürmer” (the Nazi party newspaper), available from newspaper boxes

set up in the town.

- Since the race issue is the key to our liberty, anyone who breaks

its principles shall be despised and outlawed.

The nine-member local council at that time

decided accordingly. This was followed by boycott, identification of Jewish business, placing

sentries in front of Jewish stores (to enforce the boycott), and monitoring of

people’s private lives. The slogan

“Death to the Jews” was eagerly adopted

in words, songs and pictures, and local Jewish families felt the impact as the

party slogan was subbornly observed.

Even buying essential food was made difficult for them or refused. They

were forced to wear the Jewish star on their outer clothing as a mark of racial

identification, which intimidated the affected people, so that they were

reluctant to go out in public during the daytime.

On 3 December 1938, in the Reich Gazette No.

1705, an edict was announced regarding

control of all Jewish wealth, which required that all Jewish assets be handed

over to the state. Jewish businesses had to wind up their affairs and then be

sold. A value was determined for all

Jewish-owned real estate, and the owners were required to sell within a

stipulated period of time. Possession of securities of all kinds, jewels, art

objects, etc. by Jews had to be registered with the state.

Until 1938, fifteen Jewish families paid taxes

on land, buildings or businesses. Now, however, “Aryanization” began, and

businesses, buildings and land changed owners.

Some Jewish families moved away to join their relatives in the large

cities, others sought places of refuge anywhere for their children. The whispering propaganda campaign about what

happened in the camps, and rumours of a Jewish state in the east, worried

everyone, especially those who were directly affected. Thus the Jewish

community, after existing for about 200 years, was erased and its members were

scattered. Their fate led to a deplorable

end, due to a theory of racial inferiority and a historical collective guilt of

compliance with [unjust] official routines.

It was an official routine on 19 February 1944, that set the selling

price for the Jewish cemetery at 344. RM, an amount that could be claimed by

the Jewish community after 25 years!

After the end of the war and the transfer of

power, in about 1948, the first claims for restitution came in, represented by

the Jewish Trust Corporation for Germany and, on the German side, by the

Compensation Chambers. One might suppose

that, with the settlement of material claims, the past has now been conquered

by both sides. But the deeper layers of

human relations are extremely sensitive and much more difficult to heal. Therefore, to conclude, we quote from a

letter written in 1968 by Max Goldschmidt from New York, to his former

schoolmate and friend William Hormann in Hannover, shortly before Hormann’s

death.

“I stayed in Berlin up to the time of my

emigration. Then I fled to Shanghai,China and stayed there for almost 6 years.

We were approx. 20,000 refugees. It was hopeless. After the war I went to

India, where my brother Fritz lived for over 20 years with his family. I

couldn’t stay in India, and so eventually I ended up in the United States. I am

not married and I live with my sister Änne in New York. Our mother lived to 88

years of age. I am employed in a department store and every day I work from

8:00 am to 7:00 pm.

We hear very little from Stolzenau. Kösters

wrote once. In former times Fritz Finze also wrote to us occasionally. Änne

hears from Liesel Stork regularly. Also Lieschen Schroeder (Lohgerber) writes

every year. Both of them have been here

and visited us. Liesel Löwenstein and Trude Lipmann live in New York, and we

get together from time to time. Horst, Ernst and Gerda Löwenstein live in

Washington. Erich and Hansmartin Lipmann are also in the USA. In my brief

vacations I mostly stay in this country. Last summer I was in Mexico. I liked

it there a lot. Here I meet people from all over the world, and I don’t think I

could live in Germany any more.”

The usual conclusion to this this letter is

followed by a postscript: “Please write back!”

Last note: In the late summer of 1970 Liesel

Löwenstein from New York, with her husband, came to Stolzenau for one day, and

after visiting her father’s grave, spent some very lively hours with former

acquaintances and schoolmates.