History of the Jews in

Stolzenau

by Norman Streat

The small town of Stolzenau, located beside the Weser River about 46 km

west-north-west of Hannover, has existed since the 1300’s as the place of

residence of the Counts of Hoya. The

town was affected by the Thirty Years War (1618-48), a struggle between German

Protestant princes and their foreign allies (France, Sweden, Denmark, England)

against the Austrian ruling family, the Habsburgs, who were allied with the

Catholic princes of Germany. In 1625

Stolzenau was conquered by the Catholic Habsburg forces and then reconquered by

the Protestant Danes. These events caused great suffering among the native

population. The economic, social, and

cultural consequences of the Thirty Years War were vast, with German towns and

villages being the principal victims. Uncertainty, fear, disruption, and

brutality marked everyday life and remained a memory in German consciousness

for centuries.

Stolzenau was less affected by the Seven Years War (1756-63) which

established Prussian supremacy in this region.

However it was once again affected by Napoleon’s conquests which began

in 1803. French forces conquered

Hannover in 1807 and it remained under French rule until 1813. Following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo

the Kingdom of Hannover was restored to Hannoverian rule in 1815.

A

history of the Jews in Stolzenau was written by Dr. Fritz Goldschmidt (a second

cousin of the author’s mother). Documentary

records show that Jews were living in Stolzenau in 1702, but they may have

lived there much longer. It is believed

that the Jews of Stolzenau originally came from the larger town of Hildesheim,

where they lived for several centuries under the protection of the bishops, in

an area known as Moritzberg. Prior to

that it is believed they came from southern Germany. Under the political climate which existed it was not uncommon for

the Jews to be expelled from a town and be forced to move out to the surrounding

countryside. It was possibly such an

event that caused the first Jews to settle in Stolzenau.

Up

to the 19th century, few connections were maintained to the many other Jewish

communities in the neighbouring area.

Perhaps there was a political reason for this: Stolzenau belonged to the

County of Hoya, while neighbouring Schlüsselburg belonged to the Kingdom of

Westphalia, which later became part of Prussia. Both places were fortresses until the end of the 17th

century. Symbolically, the Eruv was on the border between the two

“enemy” territories, with the result that the Shabbat zone corresponded to the

regional boundary.

A

complete description of all the Jewish inhabitants of the town of Stolzenau was

prepared in 1816. In that year a total

of 74 Jews were listed (adults and children), comprising 9 extended families

occupying 19 households (some families occupied more than one household). Detailed records of the births, marriages

and deaths in the Jewish community have been preserved for the years 1831 -

1873. By 1867, the Jewish community had

increased in population to 106 but there were still only 11 extended

families. New households were

established as children married and started families of their own. In 1858 there were 24 Jewish households in

Stolzenau.

The

1816 records indicate that the Judenschutz

laws were not always followed to the letter.

Of the 19 households only 10 had a Protection Letter - the others were

living in Stolzenau illegally. Yet the

unprotected Jews were evidently not deterred from engaging in business, getting

married and having children. It is

likely this was a legacy from the period of French rule, approx. 1807 - 1813,

when the Judenschutz laws were

suspended. The authorities may have

tightened up the laws after 1816, because the records from a few years later

show that many of these unprotected Jews and their families had moved away.

According

to Fritz Goldschmidt, the Jewish school in Stolzenau was established much

earlier, and in the late 18th century it attracted Jewish students from a wide

area who studied Talmud under teachers Yechiel Hildesheimer and Samuel Levi Goldschmidt. At this time, because the

community was not prosperous, the only Jewish institutions were the school and

the cemetery. In 1816 it is recorded

that the Jews in Stolzenau owned a house which they used for prayer services,

and on High Holydays other Jews from the neighbouring villages of Leese,

Nenndorf, Schüsselburg and Uchte would join them for services. The community employed a Schächter, or ritual slaughterer, who

also functioned as prayer leader and teacher.

In 1816 his name was Jonas Eisenberg, and he came from Galicia.

In

1834, as the prosperity of the community increased, a more substantial

synagogue and adjoining school were built.

The synagogue was the centre point of the community.

The

synagogue is poignantly described by Fritz Goldschmidt:

“The Shul, as plain as it was, possessed a

special magic for us; it was a small room with a vaulted ceiling and two

columns at the entrance as well as two columns in front of the Holy Ark. From the ceiling hung three iron candelabras,

the middle one over the dais, which was reached by climbing three steps made of

simple pine. The prayer-table was at

chest height, and in front of every person's place was a candle holder. The women's Shul was a gallery reached by a stairway off the hall. It was a festive sight, on a Friday evening

or a Yom Tov, to see the Shul shining with the light of a hundred

burning candles. But we can also

remember how cosy the Shul used to be

on weekday winter evenings, when it was barely lit by a just a few candles.”

On the right hand side of the building was the schoolroom. Up to 1925 it housed the Jewish elementary school. In the 1880s more than 80 children were taught here, all in one room. A small room located on the upper floor served as a bedroom for the teacher.

Stolzenau

had about 1,700 inhabitants towards the end of the 19th century, therefore the

100 or so Jews made up about 6% of the population. Since the vast majority of the population was Lutheran (there

were very few Catholics), Jews formed the largest minority religious group.

In

the 18th and 19th centuries most of the Jewish men in Stolzenau described their

occupation as merchant (Kaufmann) or

dealer (Handelsmann). Kaufmann

implied a higher class business than that of a Handelsmann. In many cases

they would have traded cattle and agricultural products. Several Jews were butchers (Schlachter). There were at least six and

possibly eight Jewish butchers in Stolzenau in the mid 19th century. Since there were more Jewish butchers than

were needed by the Jewish community alone, we can deduce that their customers

also included the non-Jewish population.

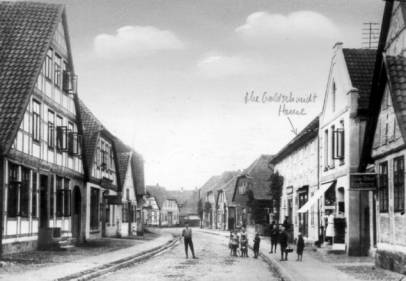

Street Scene

in Stolzenau, circa 1920

Between 1873 and 1904 the Jewish population of Stolzenau remained essentially level as children were born but people also began moving away to the major cities, notably Hannover and Berlin. From 1833 to 1905 the general population in the district more than doubled, while the number of Jews increased only slightly - thus the percentage of Jews fell from 1.2% to 0.6% of the total. By 1925 the number of Jews in Stolzenau had fallen substantially to 52, comprising just 7 families. Goldschmidts were still present at that time.

|

|

The

picture at the left shows Leo Goldschmidt’s store in Stolzenau. Leo (born in Stolzenau in 1867) is

standing in the doorway. From left to

right the children are Anni, Kurt, and Max standing together, with Grete in

the lighter coloured apron, to the right.

Lore, aged approx. 3, is futher to the right, holding on to her

mother’s skirt. The

goods in the store window are mainly clothing. The person looking out of the window at the left is Leo

Goldschmidt’s assistant, Seelig. Leo Goldschmidt and his family left Stolzenau in 1912. |

|

Leo Goldschmidt’s store in Stolzenau circa 1911 |

|

On

November 9, 1938 the Stolzenau synagogue, which had been maintained in its original

condition for more than 100 years, was attacked in the Nazi pogrom known as Kristallnacht. The Torah scrolls were

taken out into the market place and burned.

On seeing the burning synagogue, the oldest Jew of Stolzenau, Bernhard

Weinberg, was stricken by a heart

attack and died on the spot. In the following days the damaged synagogue was

leveled by dynamite.

On

11 November 1938 the local newspaper, the Stolzenauer Wochenblatt, reported the

events in a typically malicious and untruthful style:

“Also in our

home town the cowardly assassination of embassy official vom Rath, committed in

Paris by a Jewish emigrant, unleashed deep sorrow and embitterment at the

actions of the Jews. In all small towns

where Jews can still be found there were spontaneous anti-Jewish demonstrations

in which the German People expressed their indignation.

The

Jews received a response to their criminal behaviour in our district too. While its windows remain whole, their synagogue

has been completely emptied and cleared.

Only the external wall remains standing of a building in which the

hate-filled teachings of the Talmud were taught. We hope this foreign body in our community will soon disappear

entirely. Even though the members of

the German People felt considerable indignation at the shameless behaviour of

the Jews, not a hair on their heads was disturbed. To ensure their own safety, all Jews who still live in our

district were taken into protective custody.

There was no looting whatever, since everywhere SA-men ensured that no

unauthorized persons forced their way into the homes of the Jews.”

By

1940 there were just 13 Jews left in the town.

They were all deported by the Nazis.

Several days before their deportation they were ordered to assemble at

the house of Selig Blumenfeld, the last leader of the community.

They stayed there a few days until one morning a truck from Nienburg

arrived, loaded up the Jews and disappeared over the Weser bridge.

The

names of several of these last Stolzenau Jews can be found on 1941 and 1942

deportation lists from Hannover to the concentration camps at Riga and

Theresienstadt, and also to the Warsaw Ghetto.

None survived.