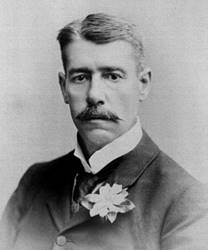

Dr. Sydney Olive BISHOP |

||||

(6 Feb 1848 – 17 Feb 1917) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Sydney Olive BISHOP was the third son of John Skinner Egerton BISHOP. He was born on 6 Feb 1848 in London, and died on 17 Feb 1917 in Hampshire at the age of 69. He was buried at Knowle Hospital cemetery in Fareham, Hampshire.

Shortly after his death the British Medical Journal published an obituary. It said “[Dr. Bishop] was educated at St. Bartholemew’s Hospital and took the diplomas of MRCS [Member of the Royal College of Surgeons] in 1872 and LRCSEdin [Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh] in 1873. He afterwards went to India, where he served for many years as a planter’s doctor in Assam, on the Houajan-Dolaguri and other tea estates, and for some time as medical officer of the Golaghat district. He also practised for some years at Darjeeling. He was the author of a small book called Sketches in Assam, published about 1885.”

He also travelled to South America and worked as a surgeon in the Peruvian Navy. In 1909 he published a book which he titled A Touch of Liver. It contains a number of anecdotes about life in India; in the Peruvian Navy; about getting from South America to Liverpool; and about "London in the Sixties".

On the internet one can find a letter to the editor he submitted to “The Lancet”, dated May 1873. In it, he discusses his experience using chloral hydrate (a sedative) to treat mental patients. The letter gives his position at that time: Resident Medical Officer, Fisherton Asylum, Salisbury. Fisherton House Asylum was the largest private madhouse (as they were then called) in the UK in the 19th century.

It has been reported that he was married at one point, but there is no further information. He had no children.

On his death, Sydney Olive Bishop left his estate to his four brothers Henry, Ernest, Herbert, and Arthur, plus he left several bequests in the form of lifetime annuities, including one to a young South American woman. This tied up the will for the next 70 years. As reported by Victor Bishop, who became a trustee of Sydney Olive’s will, it might have been possible to wind up his estate much earlier if it had been possible to buy an annuity from an insurance company to support this bequest, but unfortunately, this was not possible. The annuitant had no birth certificate, therefore no insurance company would sell an annuity without firm evidence of age. Thus, Sydney Olive's estate could not be distributed to the “issue” (descendants) of his four brothers until this annuitant died – which did not occur until 1987. By this time the descendants of Henry, Ernest, and Herbert had multiplied and had to be traced (Arthur had no surviving descendants in 1987). The Australian descendants of Herbert were fairly easy to trace, because Victor Bishop had been in touch with his second cousins Peter Bishop and Anne Fitzhardinge. But contact had been lost with Henry's descendants in South Africa and with both the Canadian and UK descendants of Ernest. They were located only after much effort was expended.

The family tree of John Skynner Egerton BISHOP is largely a result of tracing all these descendants. Sidney Olive’s estate was ultimately distributed to approximately 140 descendants of his brothers Henry, Ernest and Herbert. |

||||